A couple of months ago, we wrote this article as a response to the increase in racial discrimination, particularly around Asian Australians, during Coronavirus. The piece was unfortunately never published and within the next month, discussions about racism rapidly increased following the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent amplification of the Black Lives Matter movement. We have chosen now to publish this article here – in hopes that it resonates.

We are working on ways that we can continue to discuss racism and more importantly, racism prevention, with the wider community.

Further, Katrina Irawati-Graham, Emily Yu Zong and Anoushka Dowling participated in a virtual panel session for the Australian National University discussing the topic (link to the recording here).

Racism prevention is a vital topic here at MATE, and the current conversation driven by Black Lives Matter highlights once again the incredibly important role that bystanders play.

We look forward to continuing these conversations with our community.

—————–

The Covid-19 pandemic has resurrected a wave of racism and hate crimes in multicultural Australia, revealing the Lucky Country is not yet done with its racist past, even when it seems to have handled the pandemic better than most countries. A number of people of Asian backgrounds—especially Chinese and East Asian—have become targets of blatant or causal racism in recent weeks. As of 23 April 2020, the Covid-19 Racism Incident Survey received 240 cases and 81% were directly linked to the pandemic.

Many of the recent racist abuse have been made on Chinese Australians who had not been to Wuhan or China since the pandemic began, such as Gold Coast Surgeon Rhea Liang’s experience. Once again race marks who belongs and does not belong in Australia.

Unfortunately, racist behaviour won’t just magically disappear. The broader community needs to get involved. As advocated by the Australian Human Rights Commission, bystander anti-racism is crucial in shifting the burden of dealing with racism away from targets of racism to the broader society. One common response we hear from victims of racial attacks is “I never thought it would happen to me!” It takes ongoing and often difficult community work to start making change in deep histories of racism. Ordinary people need to be willing to be bystander activists

Disease Racism

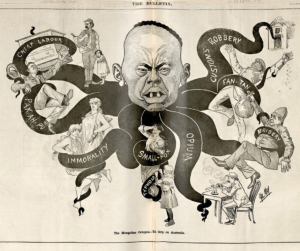

Fears of infectious disease have long been used to support racial exclusion. In 2009, xenophobic citizens in the United States blamed Mexican and Latino Americans for bringing the H1N1 virus across the border. In 19th century Australia, Chinese immigrants were stereotyped as carriers of smallpox and leprosy. In 1886 Sydney, The Bulletin published a racist cartoon entitled “The Mongolian Octopus–His Grip on Australia”, featuring a Chinese head on an octopus body that thrashes eight tentacles of crimes which Chinese immigrants were allegedly bringing into Australia: gambling, robbery, bribery, cheap labour, immorality, typhoid, small pox, and opium.

In the cartoon, the crime of “cheap labour” exposes how the fear of disease is fuelled by competition over jobs between immigrants and white Australians. This way of thinking is currently being repeated with fears of Chinese immigrants stripping Australian supermarkets of supplies and Labour’s call to “put Australian jobs first” by curtailing immigration in the post-Covid-19 economy.

Age-old racism and its Covid-19 manifestation indicate an ongoing crisis in Australian multiculturalism. While Australia is increasingly multicultural in demographics and the everyday reality of restaurants, festivals, and shopping malls, ethnic minorities of Australia hardly feature in its national myths.

Racism exposes the limits of multiculturalism in Australia. A bottom-up approach of bystander anti-racism at individual, institutional, and communal levels can help achieve the values of multiculturalism. The Covid-19 pandemic tests Australian social cohesion, but it also offers an opportunity for reinventing the Australian national identity as truly multicultural.

Tensions in Official Multiculturalism

As an official policy that celebrates ethnic inclusion and cultural diversity, multiculturalism was endorsed in 1973 by the Whitlam Government. Its introduction ended the White Australia Policy (1901-1972) that excluded non-European immigration and the policy of assimilation in the post-World War II years. Official multiculturalism not only responds to the migrant need for welfare and public services, but also the need to maintain cultural, linguistic, and religious heritage. It is relevant to social cohesion in strengthening Australian values: equal opportunity, democracy, and the fair go. Symbolically, it celebrates a new image of the nation built on unity in diversity.

However, official multiculturalism so far has not been able to resolve the tension between cultural diversity and nationhood in Australia. Anthropologist Ghassan Hage uses the term “white nation fantasy” to expose how official multiculturalism positions whiteness in the centre and ethnic cultures on the margins, the former tolerating, and enriched by, the latter. Through the language of tolerance and enrichment, ethnic minorities contribute to Australia, but are excluded from being “real Australians.” A frustrating example is the absence of ethnic groups in quintessential narratives of the Australian nation. For instance, the 213 Chinese Australian Anzac soldiers who served during World War I are rarely mentioned, let alone commemorated, in public broadcasts.

The unresolved tension in official multiculturalism can be eloquently felt in the contradiction between two sets of data: in the 2018 Scanlon Foundation survey, the majority Australian (83%) expressed that multiculturalism has been good for Australia; whereas in the 2015-2016 Challenging Racism Project survey, almost half (48.7%) of respondents supported assimilation and the view that Australia is weakened by ethnic people sticking to their “old ways.” This means that official multiculturalism has not sufficiently challenged assimilationist attitudes and white privilege.

So far under official multiculturalism in Australia, ethnic minorities are appreciated as long as they do not challenge the dominant white group. When the balance is disrupted, as seen in the threat of coronavirus from Chinese Australians, values of cultural diversity are withdrawn and white supremacy tries to regain control through racist behaviour. In other words, cultural diversity is not yet the bulk element that make up the Australian national identity.

Bystander Activism

To use a medical metaphor, we could say that bystander activism offers social anti-bodies that can help promote cultural diversity and shared values of multiculturalism in Australia. Bystander interventions into racist incidents encourage intergroup mingling and solidarity in times of crisis.

Research has shown that attitudes towards diversity in Australia and bystander action are closely related. The 2011 Victorian Bystander Survey found that people who are more open to diversity and who are confident that individuals can make a difference are more likely to take pro-social bystander action against racism. These are also people who also have a strong awareness of racial inequality and white privilege in Australia.

Bystander activism, or being an active bystander in the face of racism is challenging. It takes courage, and it takes more self-reflection than being an active bystander to any other form of violence or discrimination. Anti-racism requires us to check our privilege – to consider how we have previously contributed to systems of oppression and marginalisation and may have even benefited from them. It requires us to make peace with the times we have been complicit in our silence. It asks us to prioritise the negative impact of someone’s language or behaviour as far greater than their well-meaning intention.

As active bystanders, we can challenge these attitudes in non-confrontational ways. We can say “why do you feel that way?”, “where did you form that assumption?”, or “I don’t feel the same way about that issue”, even “I feel that this conversation is contributing to racism and its making me uncomfortable.” Holding people respectfully accountable is crucial, as is showing support to victims. Saying “what can I do to support you?”, “I want to listen to your experience”, or “I don’t share those views” sends an important message of support to the person being victimised.

Doing something in overt incidents of racism can include more practical and less personally confrontational approaches. Call the police, report the incident, record the incident, get other people to intervene with you, create a distraction. Choose something that feels safe and appropriate for you, but doing nothing is no longer an option.

We can no longer use statements like “I don’t see race”, or “I don’t know enough about race to say anything” as green lights to do nothing. Practicing anti-racism is everyone’s responsibility. The bystander approach takes the responsibility from the victim to confront the behaviour – the person being victimised should not have to be the one to challenge the racism and self-advocate. That is the role of the active bystander. Racism depends on the silence of others.

Racism is not only an individual problem. It’s a systemic and social issue. By raising awareness and encouraging action against racism, bystander interventions strengthen communal culture and build society’s resilience against crisis in general, whether it’s an infectious disease, a bushfire, flood, or anything else the nation faces.

#besomeonewhodoessomething

This article was written by Dr Emily Yu Zong, with contributions from Anoushka Dowling.

Dr Emily Zong has a research background in critical race theory, gender studies, and the Asian Australian community. She has done doctoral and postdoctoral work on multiculturalism in Australia and is passionate about promoting racial and gender equality. Her work advocates for the creative voice of Asian women and other minority groups in Australia. Emily has been a judge for the Australia China Council Book Award. Having experienced the challenges and rewards of cross-cultural living, she is committed to building cultural diversity excellence in Australia.